Summer of Hunger

Hunger Numbers in Lee County are Staggering July 26, 2010

By Francesca Donlan. May 9, 2009, 3:46 P.M.

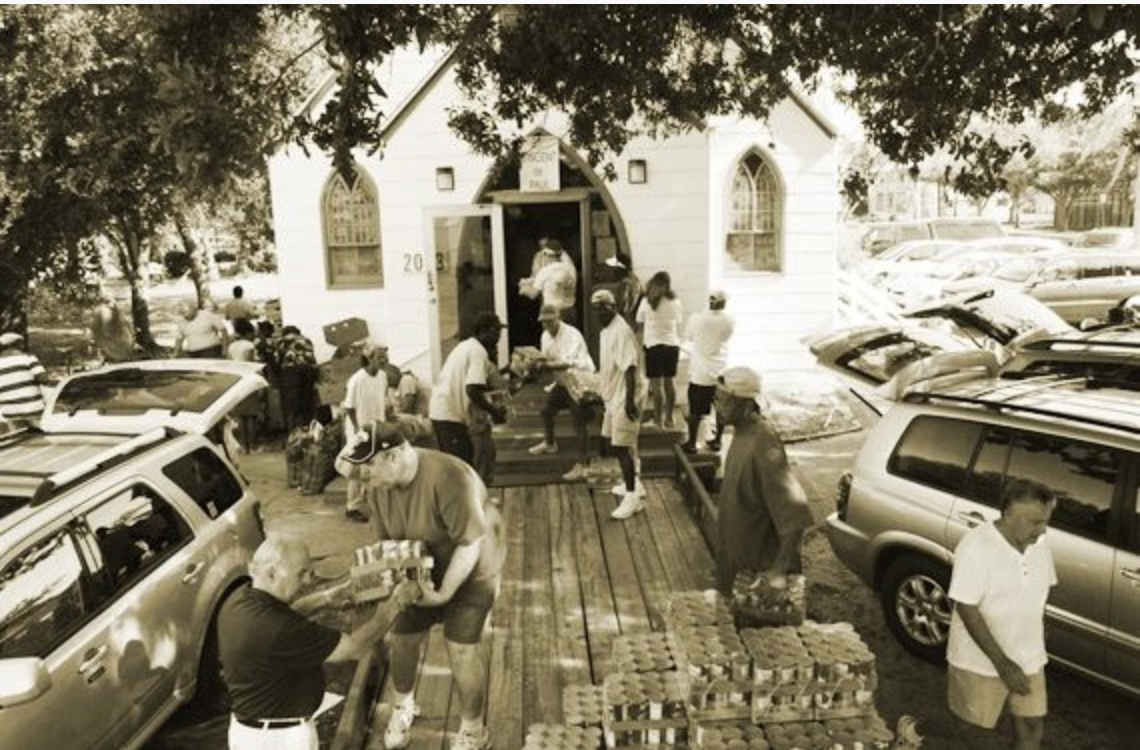

— Our food banks are overwhelmed. Our system is broken. And it all caught us unaware. Hunger has reached natural disaster proportions in Lee County — and no one saw it coming. The numbers are staggering: Nearly two-thirds of Lee County’s public school students — more than 50,000 children — receive free and reduced-cost meals. The Harry Chapin Food Bank feeds 20,000 people a month, up from 12,000 just two years ago. Applications for food stamps are up 150 percent in the past two years. “The sad part is that we’re really helping but we’re not doing enough,” said Al Brislain, CEO of the Harry Chapin Food Bank, the main food resource for Southwest Florida. The food bank serves more than 90 nonprofit organizations in Lee County. While need for food jumped 82 percent at the food bank, donations increased only 32 percent. “We’re swimming against the tide,” Brislain said. “The tide is so strong. There is so much need out there.” Lee County has been slammed by high unemployment, the highest foreclosure rates in the country and a tanking economy that pulled the rug out from under real estate and construction industries. An unprecedented number of families who never had to ask for help are hungry — thousands more than anyone ever anticipated. Lee County’s system, the feeding agencies, churches and groups that distribute food to the hungry, can’t handle the surge. “The system is broken,” said Julia East, CEO of The Southwest Florida Community Foundation. “It’s not effective or efficient.” It’s time to change, officials admit. Hunger pains As more “new hungry” poured into the system over the past two years, the churches, food pantries, and institutions that distribute food are restricted by outdated rules, regulations, resources and inability to respond. While schools are stepping up to feed children whether they can pay or not, most of the feeding agencies can’t get the food to all the people who need it. Most of the agencies work independently, don’t have partnerships or share inventory. There is no central database to track need or help clients. Rules and regulations often make it difficult for those in need to find enough food. The Hunger Task Force of Southwest Florida organized last year to solve growing hunger problems when unemployment was a mere 6 percent. Now it’s 12.2 percent. But the same group solving the hunger problem is also largely responsible for feeding massive amounts of people. Many of those on the task force are employed or sit on boards of the hunger agencies. “It’s hard to focus on the fix when bleeding is going on,”said Jo Anna Bradshaw, chair of the task force. Leaders of area feeding agencies have had a history of being territorial. Some churches serve only their congregations, some feeding agencies won’t share resources and others argue over food drives. “No more fiefdoms,” said Sam Galloway, who founded the area’s soup kitchen in 1984. He has amassed more than two months of food at his Ford dealership to feed the hungry this summer. “Get the walls knocked down. Let’s go arm and arm together.” The food agencies need to cooperate and walk in the same direction, he said. “Our world has changed drastically,” he said. “I never saw this coming and I’ve never seen anything like it.” Working together The agencies also have to change how they work. Decades of feeding the hungry the same way — eating in parks and lining up for food — does not work. New populations of hungry, being called “the new hungry,” need services that provide privacy and dignity. Families like the King family in Lehigh Acres are identified as the “new hungry” because they never before have asked for services. “I’m in construction. Everyone I talk to is belly up,” said Ben King, 31. “I’m losing money working 10 to 12 hours a day. That’s the economy I’m working in.” King made $125,000 a year in his construction business before the economy crashed. Since then his family has gone through its IRA, savings, credit cards. This year he is $40,000 in debt. For the first time he and his wife, Brooke, have had to get assistance to buy groceries for their three sons. “There’s nothing to do now but get up at 4:45 a.m. and make it happen,” King said. ”Do a $3,000 paint job for $800. Nobody’s making anything, but what are you going to do?” Fixing the system Lee County isn’t the only area suffering. Feeding America, the nation’s leading hunger-relief agency, provides food to 200 food banks, including Harry Chapin Food Bank. It’s sent “millions and millions” more pounds of food to feeding agencies, said Ross Fraser, spokesman for Feeding America based in Chicago. ”The need for food is up an average 30 percent with some food banks reporting much higher,” Ross said. ”Places like Florida, Ohio, Michigan, and California are through the roof.” Dave Kropche, CEO of Second Harvest Food Bank of Central Florida, operates at a “disaster relief level” with a 20 percent increase in need. He calls the 82 percent increase at the Harry Chapin Food Bank “horrific.” “Some areas have been hit hard but unfortunately for Lee County it’s been disproportionately hard-hit,” Kropche said. The need came as a surprise. ”It hit us so hard and so quickly,” Bradshaw said. “If we had been prepared for this two years ago we wouldn’t be in this position.” But no one expected hunger to strike with the same vengeance as a natural disaster, she said. Fixing a broken system is what inspired Bradshaw to chair the Hunger Task Force a year ago along with a dozen agencies directly involved in fighting hunger. The group has created long-term goals including the creation of a database of providers, finding future funding for food and advocating for legislation on behalf of hunger issues. But its long-term goals don’t solve today’s hunger crisis. And little progress has been made toward those goals in the last year. The problem is solvable, said Sarah Owen, executive director of Cooperative Community Ministries Inc., which oversees agencies including The Soup Kitchen and Meals on Wheels in Fort Myers. “The community has the wherewithal to fix this,” she said. “I’ve seen them do it before during a natural disaster and at other critical times. People do band together to solve a problem.” Galloway is tired of talking about the hungry. He’s determined to get food to people who need it. ”We have to work together,” he said. “Kids need food now. We have to decide how we’re going to win this thing. We’ve got to get it done.” Original article located at www.news-press.com.